Creative types are often visual people. And there is nothing more visual than drawing. As the voice is our one built-in instrument for our hearing, so is hand-drawing the main expression for vision.

Using our own hand to sketch out an idea is a natural step for our creativity.

So I constantly draw pictures, drawing on my creativity to help me visualize. And it is a salve for the rougher times of our lives. A bit of escapism. Good for what ails us.

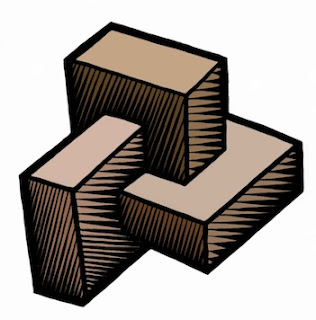

3D Forms

Ironically, it is two-dimensional pen and paper that becomes the practice field for

three-dimensional cognition. I know I am constantly drawing forms and shapes, trying to figure them out or reason about their volume. I imagine holding them in my hand, reorienting them, looking at them. And then I draw.

And when I draw, I try to find the proper orientation to depict the object and show its own characteristic features in the best light.

For a cube, I almost never draw it in such a way that I can't see its inherent dimensionality. For a snub cube, I show the snub facing the viewer. Otherwise I probably can't tell what it is. So I reorient the object in my mind to draw it.

I like the idea of something having a real three-dimensional heft to it. I can almost feel the edges around the missing corner.

Other objects are equally interesting. I like, for instance, to imagine how objects intersect, or how other objects can be contained inside them.

It isn't well-known, but the dodecahedrons - both the platonic one and the rhombic one - can superscribe a cube. This shape is the basis of a garnet crystal.

I show a rhombic dodecahedron superscribing a cube. Imagine a cube with short pyramids on each face. Constructing one with pencil and paper is easy, since the height of each pyramid is exactly one-half a cube edge length.

Rhombic dodecahedra can fit together and tile space perfectly like cubes, which I find interesting. And it's also obvious, since the vertex of the rhombic dodecahedron is actually at the center of a neighboring cube.

There are plenty of shapes that I have drawn over the years, most of them are found on the backs of meeting notes or on Excel spreadsheet printouts.

I can't even say what all the objects are, but I did find them interesting to imagine at one point. Perhaps this is a button from an old corduroy jacket.

On the same sheet I found another drawing. What is this trying to be? I imagine it is a folded bit of paper, arranged in a triangle. I never showed its other side, and so that remains a mystery.

At some point, though, three-dimensional figures need to be transcended. This is done by imagination and also by requirement. Imagination and simple tinkering can lead to the impossible figure. Requirement can lead to icons. They are both interesting pastimes and also they can be real work, as we will see.

John Derry and I spent many, many hours searching for the right icons for brushes, for features of brushes, for effects, for tools, for everything.

Impossible Figures

I have written about impossible figures before. But I created one in 1969 based on the impossible triangle. I drew the Triangular Symbol in summer 1969 when I was but 13 years old.

I drew it only a couple of months after my grandfather died, so it was clear that my obsession with impossible figures might have come from my

need to process the situation.

It was drawn with a Flair pen on the harshest Olivetti copy paper, so it has colored a bit through time. And the felt pen I used wasn't exactly the best tool to use. I used a drafting set to make the basic shapes. And then I shaded it the best I could, given it is, after all, impossible.

The draftsmen at Lockheed, where my dad worked at the time, were quite impressed and put it up on their walls. But it was a time of downsizing for Lockheed and soon they were laid off.

That was the bad news. The good news was that we picked up a nice drafting table for me, cheap.

Here is the basic impossible figure it is based on. This was originally drawn in 1934 by Swedish artist Oscar Reutersvärd and later made popular by Lionel and Roger Penrose. Though it is impossible, you can create a version of it in real space, made so you can look at it from one angle and it will look real.

This is not so for all impossible figures, though. And these definitely defy imagination. Really, the first impossible figure I ever saw was in the Time-Life book about the Mind.

This impossible figure is the one that the draftsmen liked. Before I showed them the impossible triangle.

They had this figure up on their wall right next to the drafting table as a kind of joking reference to nonsense and I respected them for their humor in the matter.

This figure can't be constructed in three-space because inside and outside exchange places, obviously. If you look at one side and then the other, they are reasonable taken by themselves. But not together as a whole.

In the post

Interlock, I discussed the Valknut, a cool figure used by the vikings around Gotland centuries ago to symbolize Odin's patronage of those who died in battle. It is a sacred mark of sorts.

I present here another impossible Valknut, one which intersects itself. This one took a couple of tries, I assure you. It is still a variation of the impossible triangle. I guess I never tire of making these variations.

In some ways, these figures are a tribute to M. C. Escher, the famous dutch artist that perfected the ever-ascending stairway and other impossible illusions.

I love his art! In some ways, I think maybe I'm almost as crazy, if not quite as

detail oriented, as Escher. He used his hand to make all his art, and that makes me respect him.

I have often thought of the ever-ascending staircase, and so I have drawn overlapping planks to simulate the feel of the original Escher piece.

I show that they have to be bolted together to hold them in place. But I'm not quite clear on their shapes. I show some warping to the planks so they can fit, but I think it is a bit more difficult to make this work. Unlike Escher, I have preserved their proportions. Escher made his work by having a different number of stairs on the four sides of the stairway. I have used no such cheat.

Still, I try to imagine the exact shapes that will make this work. And to what end? To relieve myself of the boredom of a staff meeting. Heh.

Three-Dimensional Interfaces

In Detailer, which was Painter for painting on 3D objects, I was in the business of creating icons for tools that involved movement and rotation. This was an exercise in three-dimensional thinking and icon development. It's interesting, but Phil Clevenger ended up doing much the same thing when he worked on the Bryce and Poser interfaces. And his designs were much cleaner, I think. And in some ways,

much more gothic.

Here you see a cylindrical rotation icon. For rotating a vase that you are painting, for instance. I think the cylinder in the center has to be a glass rod to make it sensible.

But this was only one of many icon tries for three-dimensional interfaces. I soon elicited John Derry's help in creating them.

I think I like three-dimensional interfaces because they simulate real objects that you can use. Like a folder that opens up when you move something to it and

whoosh, the thing goes into it.

The virtual trackball for rotating three-dimensional objects on screen is an interesting task for icon creation. I think my first idea was on the left here.

But eventually, it all got screwy. Icon creation is a really hard problem in general, because you have to develop a design language that is consistent and clean and not easily misunderstood: hard to get wrong.

While sitting in endless meetings, my mind would wander. The endless progression of a grid of beans, each with their own shadow is a good depiction of boredom. And a symbol of the sure knowledge that the group will head all together in the same direction. I can see the words

bean counter were almost certainly in my mind at this meeting.

This was drawn on the back of a spreadsheet that detailed the booth personnel hours for PC Expo in New York in 1996. It's really kind of funny, put into that perspective.

The Fractal Design sales personnel were well-meaning and extremely organized, so I shouldn't trivialize their hard work. After all, they were where the rubber hits the road! I will forever owe them a debt of gratitude!

At this point, I was still the CEO and we were a public company. But rust never sleeps, and I had products to create. And this includes being creative, even during sales meetings!

A page floats to the ground, its shadow beneath it and showing that it has just contacted the ground, or is about to. A corner is turned up. You can feel the rush of air beneath it, just before the page settles.

Three-dimensional forms in motion.

Nothing is static, all is moving. Trade shows and products must go on, as does life. At this point in January 1996, my life was changing, more like going over a waterfall, and I had just met some of the most interesting people I will ever meet in my life. Drawing, playing piano, writing songs, and even composing poetry: there were lots of issues to work out, and creativity was central to that process. Good times!

Icon Creation

It is very hard work creating icons and with its own design language, it can drive you a little crazy. John and I were designing Detailer icons one day, when we created this interesting bit of art. You can click it to get a larger version, which might be necessary to see it in all its crazy detail.

We were working on trackball icons. In the center, you see a prototype for the sphere with an arrow going around it. But John said that the arrow might best have two points on it, signifying that you could turn the object in any direction.

This led to a happy face with arrows on the mouth. I drew a vase with an arrow going around it, then drew a vase pouring out liquid with an arrow going around it! There is a cube with an arrow. And various circular arrows drawn and obliqued. Then John drew a brush with an arrow going around it. And it just got weirder from there.

Pretty soon there were atoms and icons for the funniest things. Like a dead fish icon. And a dead dog icon (?). And a lightning strike icon. And a tornado icon. The cow is floating around it, saying "moo", by the way.

We had gotten a bit crazy in the process; we tended to do this. How can you be serious when you are creating icons, after all?

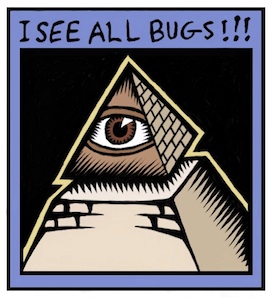

You can see a scissors-cutting-paper icon, a road-into-the-distance icon, a submerged pyramid icon, and even a bleeding eyeball icon! I think the comment was that some of these icons were so bad, it made our eyes bleed! No, we weren't actually being serious at the time at all.

One of the icons is the pyramid with an eye in the tip. This symbol is actually on the US Dollar bill. Not sure why. But I liked it, as an impenetrable symbol of, like, a secret society.

I have one that, in its unedited form, says "I SEE ALL BUGS!!!". There is a bit of humor there, since I was talking about bugs in Painter: you know, mistakes in the code that needed to be fixed. We really needed to fix all of them before any release.

This is the standing order of things at a software company. And, as a primary developer, along with Tom, it was always my main responsibility to fix the problems. In the Painter 6 time frame, I did more bug fixing than usual because Tom was preoccupied with other issues.

John and I often made whimsical icons. Like a firecracker icon (John's). Or a lit match icon (mine). These weren't icons that had any purpose being in software, that's for sure! So we were just joking around. Entering the crazy phase. Getting really loony from being in icon hell too long. In think we tried to get more and more outrageous, just as a mode of escapism and perhaps as a kind of performance art:

inappropriate art. We loved to do that.

Sometimes the icons were statements of our current situation. If we were buried in some problem that looked easy, but it was actually very, very hard, I'm sure that the iceberg icon could accurately depict our plight.

If we were outperforming our capabilities, or if we just wanted to show off, I'm also quite sure the "goes to 11" icon could make sense of it all. It is a reference to Rob Reiner's movie

This Is Spinal Tap.

If we were under water or in deep seas, we might draw the ocean icon. If we were feeling angry at the world, we might draw the gun icon. Totally out of order, gentlemen! This is not allowed!

But at the bottom of it, it wasn't ever really obvious why we drew these. They were just a way of joking around while embedding ourselves and our mindsets in the art of icon creation: an art that has its own purgatory built right into it.

Sometimes Icons are just symbols for something, and can be borrowed from the icon language of, say road signs, or caution symbology.

We also liked to play that game, of borrowing the design language from some other task. It is, after all, what the paint can is based on, and so many other cool things from Fractal Design. It's where design gets fractal.

And at the end of the day, all that mattered is that we achieved our goals to ship a product. To have a product that could rise above the monotony of mundane software products. We showed them how to do it right. We were Fractal Design, after all.

We had a

reputation to keep up!

Our brushes had to be the coolest. Our effects had to be the first on the block. Even layers came out first and we made hay with it with

make up your mind again, and again, and again. Design is not a linear process, because of trial and error but even more because the client may not like your design. And you may have to produce several designs to show the client. We got that.

Our brushes were cool because we were always thinking of what the designer wanted out of a brush stroke. Not just what the artist wanted. Because we could simulate the natural tools, and we could

also extend the capabilities of the artist directly through our new tools.

So what the designer wanted, and what we felt they would like in the future, mattered to us. We were practicing designers: we were

Fractal Design.

In 1992, when John Derry joined Fractal Design, he introduced me to the traditional scratchboard tool. And the art of designing icons! The scratchboard tool was a tool that could scratch a thin layer of black paint off a white board. It was a very specialized traditional process, involving specially-prepared scratchboard and a special tool, like a crow-quill pen, with a changeable nib for scratching the black paint off.

In 1992, when John Derry joined Fractal Design, he introduced me to the traditional scratchboard tool. And the art of designing icons! The scratchboard tool was a tool that could scratch a thin layer of black paint off a white board. It was a very specialized traditional process, involving specially-prepared scratchboard and a special tool, like a crow-quill pen, with a changeable nib for scratching the black paint off. The scratchboard tool and its digital version pushed me to create more high-contrast art that came very close to a woodcut look. Some of my pieces from 1994 and 1995 are shown in Art From Deep Inside the Psyche.

The scratchboard tool and its digital version pushed me to create more high-contrast art that came very close to a woodcut look. Some of my pieces from 1994 and 1995 are shown in Art From Deep Inside the Psyche. Here is the "Earthquake" icon. Really the ground doesn't crack open in an earthquake, though! Why is it that most earthquakes seem to happen on bright cheerful sunny days? Because I have only been in an earthquake in California, thats why!

Here is the "Earthquake" icon. Really the ground doesn't crack open in an earthquake, though! Why is it that most earthquakes seem to happen on bright cheerful sunny days? Because I have only been in an earthquake in California, thats why! A hurricane icon depicts a fierce wind, blowing trees over and flooding with its massive overpowering storm surge waves.

A hurricane icon depicts a fierce wind, blowing trees over and flooding with its massive overpowering storm surge waves. Tornados are a major destructive force of nature! Their winds lift objects weighing tons and throw them through the air, leaving a path of destruction sometimes a half-mile wide, like a scar on the earth.

Tornados are a major destructive force of nature! Their winds lift objects weighing tons and throw them through the air, leaving a path of destruction sometimes a half-mile wide, like a scar on the earth.