I hold that some disorganization, some mess, is required to get to a creative point. If a Rubik's cube couldn't be messed up, then it wouldn't be any fun to solve it. In fact, the messed-up Rubik's cube makes a nice symbol for intelligence in disarray.

I hold that some disorganization, some mess, is required to get to a creative point. If a Rubik's cube couldn't be messed up, then it wouldn't be any fun to solve it. In fact, the messed-up Rubik's cube makes a nice symbol for intelligence in disarray.While the cube provides some exercise for my mind in solving it, it also suggests that we need a mess to get into an analytical state as well. Or at least to practice our analytical side.

But the real value of mixing it up is to be presented with different things in different contexts. We night never put them together if it weren't for the mess in the first place. No, this is not about entropy and order. This is about the interconnectedness of thoughts. The complex relationships, similes, metaphors, and comparisons that our mind makes when presented with diverse options.

Operations on Ideas

One of my fields is imaging: pictures. When developing new imaging technologies, I come across many different techniques that apply to imaging. But the new techniques come from a specific set of operations on ideas that help me to cross disciplines and make something new.

The first operation is deconstruction. With this technique a problem or a subject is torn apart in different ways so we can see what it's made of. With images, this can be something like moving the image into the frequency domain. Or, it can be thinking of the image as a bunch of tiles, or a mosaic. Or re-representing an image as a Gaussian pyramid. You can think of this as the analytical pre-step in being creative. The more ways you can deconstruct something, the more likely you are to find something new.

|

| A sculpture from Napoleon's Arc du Triomphe |

This is as good a subject as any to introduce the next operation, random association. For something like directions, these associations are concepts like motion, velocity, vectors, maps, routes, paths, going the wrong way, a drunkard's path, alignment, perpendicular, turning the wheel, etc.

|

| The image processed by representing it as directions |

I use this to help me in branching out, another operation in creative ideation. If I move from directions to vector fields, for instance, I can then look at various properties of vector fields, like vorticity. I can also look at operations that apply to vector fields, like div, grad, and curl that I might never think of when I'm focused solely on images.

Or, looking at direction as a velocity vector can lead me to realize that it has length and angle. Branching out from this can lead me to realize that a direction's angle can be changed. This has dramatic consequences for imaging, since it can lead to an altered reality.

Or, looking at direction as a velocity vector can lead me to realize that it has length and angle. Branching out from this can lead me to realize that a direction's angle can be changed. This has dramatic consequences for imaging, since it can lead to an altered reality.The next creativity operation is experimentation: varying the parameters.

A picture of a tree can be quite picturesque, particularly one from the Kona coast. But when you take the directions in the image and rotate them all 40 degrees counterclockwise and mix them back into the image, you get a windswept alt-tree.

Very different from the original. By both branching out and experimenting, I have created a new effect and it has some profound visual consequences.

It so happens that this effect was accidentally discovered while working on something completely different (which I can't actually talk about)!

I will show few more pictures for the visual people among my readers.

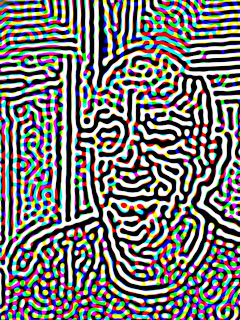

To right you see a picture of me taken about a decade ago near the Statue of Liberty. Here I have applied maybe a fifteen-degree tilt to the directions.

There is a little bit of windswept effect from the direction alteration. This is just what I was going for, and it is fortuitous. With the Arc du Triomphe image, the directions weren't altered in the least. But there is some uncertainty to evaluating directions and, when this effect is applied at a certain scale, you can see that the smallest details aren't always preserved. If they were, it wouldn't be interesting in the least.

Apply this effect to clouds and make the directions perpendicular to their usual course, and you get a puffy, almost feathery, cloud.

Apply this effect to clouds and make the directions perpendicular to their usual course, and you get a puffy, almost feathery, cloud.It's a jittery, crazy kind of reconstruction of the cloud image.

This brings me to the last operation, which isn't really about creativity, but you can be creative about how you do it, of course: reconstruction. If you have figured out what something is made of, managed to jumble it up internally, then you can reconstruct it and hopefully not end up with Frankenstein.

Can we apply this to another field as well as images? Of course! In music, I deconstruct songs typically so I can reflect on how they are made. Then I can randomly associate the structure of music with, say, grammar. And I can branch out from the usual song grammar to use multiple linking sections, or to precede each verse with a little prelude (I did this in my song Baby, I). Or rearrange the chords backwards and see how that sounds. I did try recording a backwards guitar part in one of my songs, and the interesting process is chronicled in another blog post.

Or, I can deconstruct music into inter weavings of sound and silence. I can put moments of silence into a song, to create a full stop. Perhaps a fake ending, or just a de-textured rest. Yes, I used this in I Know You Know.

I can deconstruct sound into treble, midrange, and bass and create a wall-of-sound interpretation of music. Or deconstruct vocals from instruments. Randomly associating, I can have the vocals play the instrument parts, like the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson had his band do in Help Me, Rhonda.

One of my favorite creativity groups was the Traveling Wilburys. In Handle With Care, they changed the song structure several ways. First off, the song has 2 bridges. Then the solo comes in the fourth verse, and it's only a half-solo. The full solo comes at the end, after the repeat of the two bridges. After the fifth verse.

The Evils of Organization?

While organization is important to our everyday life, too much organization can also hamper us in ideation. The principle is this: if everything is in its own little box, then you simply can't imagine something that is out of the box. Is this even true?

As impossible as it seems, even obsessive-compulsive people can make great artists. This may be because OCD leads to various interesting styles, like horror vacui. Many indications of "madness" in art have drawn us to them in the past. VanGogh and Hieronymous Bosch stand out in my mind.

And there is a place for neat freak artists as well.

But somewhere in between neat freaks and slobs are all the rest of us just trying to be creative and solve problems in a new way. Bringing a fresh approach to something is what it's all about. And disorder (mixing it up) is just one tool to accomplish that goal. Analysis is just as valid, and it is actually necessary for deconstruction.

But somewhere in between neat freaks and slobs are all the rest of us just trying to be creative and solve problems in a new way. Bringing a fresh approach to something is what it's all about. And disorder (mixing it up) is just one tool to accomplish that goal. Analysis is just as valid, and it is actually necessary for deconstruction.To properly deconstruct, you need to take a step back and look at your problem in a new way. For instance, looking at texture as geometry instead of pixels. Looking at stuff in different ways is really the true basis of creativity.

Look at this video of the Traveling Wilburys Inside Out. It's just the band playing, but you can see that they took song lyrics and looked at them in different ways. Thanks to the lyrical talents of Bob Dylan and Tom Petty. And the entire subject is inverted again in George Harrison's bridge "be careful where you're walking".

Check out my blog post on Where Do Ideas Come From to see some of these principles in practice, and the value of operating in a creative group, as the Wilburys did.