In my notes from 1997 and 1998 I found this graphic from the last days of Fractal Design, immediately after the merger with MetaTools, and the start of the newly-formed company, which was to be called MetaCreations. It shows my irreverent take on typography, with letters verging on an alien alphabet. Perhaps this was my thinking in those days, clearly influenced by Star Trek: The Next Generation design and increasingly beginning to think that aliens were taking over my company.

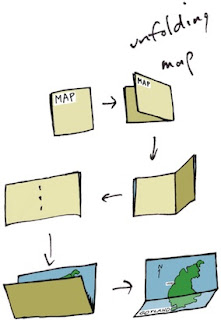

In my notes from 1997 and 1998 I found this graphic from the last days of Fractal Design, immediately after the merger with MetaTools, and the start of the newly-formed company, which was to be called MetaCreations. It shows my irreverent take on typography, with letters verging on an alien alphabet. Perhaps this was my thinking in those days, clearly influenced by Star Trek: The Next Generation design and increasingly beginning to think that aliens were taking over my company. The graphic was a last hurrah, buried in my logo-search stack. These were the papers that detail the search for a new company name and logo, begun as a result of merger. Those were turbulent days, full of interesting ideas that never made it. Here is another little sketch from that collection of the doodles drawn in those days when the meetings were long and the bickering was uncomfortable. I was already thinking about the metaphors for the idea processor.

The graphic was a last hurrah, buried in my logo-search stack. These were the papers that detail the search for a new company name and logo, begun as a result of merger. Those were turbulent days, full of interesting ideas that never made it. Here is another little sketch from that collection of the doodles drawn in those days when the meetings were long and the bickering was uncomfortable. I was already thinking about the metaphors for the idea processor.

Name search

First came the name search. The first edict, from John Wilczak (the MetaTools CEO and soon to be replaced) was that the name should contain "Meta". Once you put that flag in the ground, there are only so many names that can be chosen. We all bought into it.

John Derry and I thought up several meta-rooted names for the company. We centered around various concepts, like making: names like metaforge, metafactory, and metaforce. We also tried words around branding: names like metabrand, metaware, metafactor, and metacraft. Next we covered concept names like metapath, metaform, and metadesign. Of course, we also looked at location names like metaworld, metastage, metasphere, metawave, and metalevel. Combination names sometimes became useful, like metalith and metastar. We were going for simplicity and pith.

We had a hundred names to choose from, and three or four made the top of the list. But it turned out that they were always taken by one company or another, and so proved themselves to be unsuitable for our purposes.

In the end, the root word meta (meaning "on another level") was merged with "create" and we somehow found MetaCreations as our new name. We worked out the typestyle, using a PR branding firm called 30SIXTY, contracted by Sallie Olmstead. The result was a very good type treatment. One of their designs stuck, seen here. MetaCreations passed the trademark search and so we found ourselves in the position of needing a good catchphrase to go with it.

In the end, the root word meta (meaning "on another level") was merged with "create" and we somehow found MetaCreations as our new name. We worked out the typestyle, using a PR branding firm called 30SIXTY, contracted by Sallie Olmstead. The result was a very good type treatment. One of their designs stuck, seen here. MetaCreations passed the trademark search and so we found ourselves in the position of needing a good catchphrase to go with it.

Catchphrase and Logo

At this point, we hired a new CEO and the branding began afresh. This cast us into disarray: the implications of three separate groups pushing in different directions. Let me introduce you to the three groups:

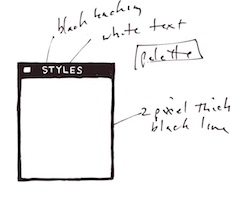

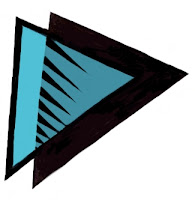

One group was Gary Lauer's group. Gary was the new CEO, hired by the board and taking on the challenge of merging two cultures with a third culture of his own. The second group was Kai Krause's group. Kai was the design thinker from MetaTools and the creative face of the company. The third group was John Derry and myself, Mark Zimmer. But, frankly, I took the lead because I was the representative to the logo group. As you will see, the three groups couldn't agree less. And yet we eventually found a logo. Here I show a doodle from a page drawn during the endless logo meetings.

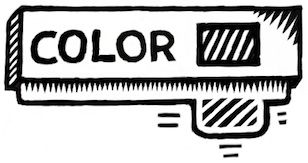

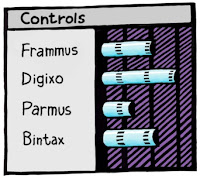

One group was Gary Lauer's group. Gary was the new CEO, hired by the board and taking on the challenge of merging two cultures with a third culture of his own. The second group was Kai Krause's group. Kai was the design thinker from MetaTools and the creative face of the company. The third group was John Derry and myself, Mark Zimmer. But, frankly, I took the lead because I was the representative to the logo group. As you will see, the three groups couldn't agree less. And yet we eventually found a logo. Here I show a doodle from a page drawn during the endless logo meetings. The catchphrase Gary preferred was staid and traditional: The Visual Computing Software Company. The logos from his group were not unlike the ones from Claris in style. The other two groups saw the logos as pedestrian and frankly uninteresting. Here you can see one of the color schemes of his final logo set. The earlier ones were considerably more amateurish. This one features an M-shape with a bit of a shine nestling into it. My comments on this particular logo are unprintable, sadly: I will leave them to your imagination. Kai felt pretty much the same about this logo.

The catchphrase Gary preferred was staid and traditional: The Visual Computing Software Company. The logos from his group were not unlike the ones from Claris in style. The other two groups saw the logos as pedestrian and frankly uninteresting. Here you can see one of the color schemes of his final logo set. The earlier ones were considerably more amateurish. This one features an M-shape with a bit of a shine nestling into it. My comments on this particular logo are unprintable, sadly: I will leave them to your imagination. Kai felt pretty much the same about this logo. The catchphrase Kai preferred was genuinely clever: where great ideas are born. Also, John Wilczak, before he left, preferred start the migration, though I'm still not sure where he was going with that one. The logos from Kai's group initially centered on an egg - with the idea of hatching a new idea. Other groups just kept thinking "Meta lays an egg" as the headline. After a brief trademark search, we discovered Software Ventures had an egg with a shadow as its logo, and that was the final crack.

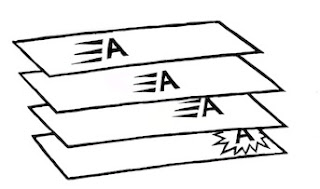

The catchphrase Kai preferred was genuinely clever: where great ideas are born. Also, John Wilczak, before he left, preferred start the migration, though I'm still not sure where he was going with that one. The logos from Kai's group initially centered on an egg - with the idea of hatching a new idea. Other groups just kept thinking "Meta lays an egg" as the headline. After a brief trademark search, we discovered Software Ventures had an egg with a shadow as its logo, and that was the final crack. In the sessions for my group, John and I tossed around the creativity concept endlessly. One catchphrase was bringing creativity to you. Another was changing the way people think. Our final try was sparking your creativity. While fascinating and very ambitious, I still think Kai's catchphrase was best. Our logo designs centered on a hand - for software that was human-centric. The hand was the artist's signature from the days of the cave-painters. Other groups just saw "stop" - a hand telling you not to enter. Here, we placed it inside an oval form to suggest an egg.

In the sessions for my group, John and I tossed around the creativity concept endlessly. One catchphrase was bringing creativity to you. Another was changing the way people think. Our final try was sparking your creativity. While fascinating and very ambitious, I still think Kai's catchphrase was best. Our logo designs centered on a hand - for software that was human-centric. The hand was the artist's signature from the days of the cave-painters. Other groups just saw "stop" - a hand telling you not to enter. Here, we placed it inside an oval form to suggest an egg.

All three groups had a basic problem - the other two groups opposed their design. So Gary, thinking his group was more equal than the other two, decided to make a presentation of his logo. Allowing us to choose the color scheme. Ah, that was a rough meeting.

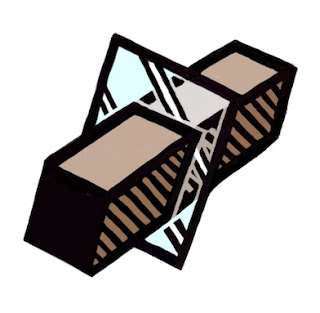

This required Kai and I to work together on a new logo. I dredged up an old design: the trefoil knot. I had made this design in 1983 when working as a consultant for Auto-Trol (I was building them a 3D system for computer-aided engineering). I had resurrected this design when working on Detailer, the 3D Paint Program, adding a mirrored surface to it. Here we see a small version of this knot, produced in Detailer using a brassy look. Kai's people used Bryce to create a much cleaner, smoother nicely-tilted version of this knot, and added a slight soft shadow underneath it.

This required Kai and I to work together on a new logo. I dredged up an old design: the trefoil knot. I had made this design in 1983 when working as a consultant for Auto-Trol (I was building them a 3D system for computer-aided engineering). I had resurrected this design when working on Detailer, the 3D Paint Program, adding a mirrored surface to it. Here we see a small version of this knot, produced in Detailer using a brassy look. Kai's people used Bryce to create a much cleaner, smoother nicely-tilted version of this knot, and added a slight soft shadow underneath it.This shadow was eventually omitted and the catchphrase was changed once again.

This time I wasn't asked. As you can see, it became The Creative Web Company. The times were changing, and at this time, before the dot-com boom and collapse, everything had to be naively covered with web-web-web. The trefoil knot had a nice reflection and self-shadowing, though. Kai and I approved the form.

After Kai and I decided to redesign the logo, he had his people design some new forms. Many of them were based on threefold symmetry, which I also tend to prefer. One designer, Athena Kekenes, produced some iconic figures that still hold up today. The first figures were triangular-symmetry organic forms that had a very interesting, yet somehow alien, lilt to them. With tree-like branching properties and spherical ends, it looked a bit like some strange form of sea-weed. You can see one of the designs here. We asked for some more ideas.

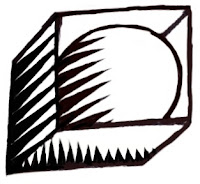

One was a cube that had a sphere subtracted from it. This, when viewed from the direction of a corner, had a six-fold symmetry that was quite pleasing.

Here you can see the cube, with the sphere subtracted. With Boolean operations in Bryce, this stuff just jumped right out of the imagination into the page.

When you look at it, it's a bit busy. It has a shadow, the three visible sides of the cube have different shades. The sphere has gradations. The objects even shadows itself!

I'm sure this is what Kai and Athena were thinking when they came up with the simpler version of the logo.

Here we can see the flower logo. It's very clean, simple, stylistic, and suggestive of 3D.

Negative space is used in two ways: the sphere is negative space when subtracted from the cube, and the flower is the result of looking through the negative space of the 3D form and coloring in the holes.

In some way, though, we found these cube-based logos to be too derivative of the Silicon Graphics logo. I even found the SGI logo in my notes right next to this one.

Here is an egg-derived logo that used the shape several times in negative and positive space to form an op-art logo. This held up better because it could be reproduced in black-and-white. As any good logo should.

But eventually we centered on the trefoil knot. It's iconic form was clear. Before any of his people had a chance to perfect the trefoil with reflections and shadows, he had his people do special black-and-white versions of the trefoil.

This version is exceptionally clever, using rotated versions of the knot silhouette in alternating colors, then subtracting out the middle.

Though we liked the line art reproduce-ability of this form, we thought it looked a bit too much like the woolmark logo.

In all, we spent too much time working on the logo. Gary, in his desperation, did an end-around and created his own logo and placed it on our products. This was done because, after all, we had to have something to put on shipping products. This was another logo based on the M (and, it seems, on Freddy Krueger).

As you can see, Gary even replaced the typeface we selected! His quest for a unified package design was next. This actually made us mad, because each product was a brand of its own and the entire concept of unified product packaging design seemed wrong.

What did we do to deserve this?

In all, I wasn't really satisfied with what came out of this process. Personally, I doubt Kai was either. Meta continued to create great products, nonetheless. Bryce, Painter, KPT, and Poser saw fantastic new versions. And Ray Dream Designer metamorphosed into Carrara, which was a very ambitious project and a great product in its own right.

And I just kept drawing new iconic logo designs. I knew that someday they might be useful to me. And someday the story would be told.