This post talks about the Painter can!

At Fractal Design, one of the most interesting stories is that of our innovative packaging. You see, we were into skeuomorphic design. And there's an easy explanation: we strove to make the entire product more like the real world because we were also doing the same thing with our paint and drawing tools.

In Dabbler (Art Dabbler in some countries) we worked on the wood grain of the interface. Sketcher shipped in a cigar box. This is because artists and designers often used a cigar box to store their art supplies (but they probably didn't smoke the cigars, at least while I watched). The paint can was just another reference to the real world of paint.

As for how this came about, well, it all started with a presentation from Hal Rucker and Cleo Huggins from Rucker/Huggins design to Fractal Design in 1991. Present from Fractal Design were myself, Tom Hedges, Steve Manousos, and Steve Thomas. At that time, we were most of the board of directors (along with Lee Lorenzen) and also most of the executive staff (I was President and CEO, Tom Hedges was VP or R&D, Steve Manousos was VP of Operations and Sales, and Steve Thomas was VP of Marketing).

Anyway, in that presentation, we were shown six options for packaging. Our job was to choose one. They were all stored in bags so we couldn't see the mock-ups, and revealed one at a time.

The first option was a conventional "Adobe Style" turned-edge fiberboard box. Their comments were:

The first option was a conventional "Adobe Style" turned-edge fiberboard box. Their comments were:proven reliable manufacturing technology (few unknowns)

high quality look and feel: printing and dense material

Painter could get lost on the retail shelf: too similar to others

It worked out to between $7.00 to $12.00 per unit (plus inserts), and it of course depended upon quantity, size, printing extras, and manufacturing extras.

We could see that this was standard operating procedure. After all, ImageStudio, ColorStudio, Illustrator and Photoshop all used this mode of packaging. Others used cheaper kinds of packaging, with less panache, which was to follow.

The second option was a conventional "paperboard" box. And here, their comments were:

The second option was a conventional "paperboard" box. And here, their comments were:proven reliable manufacturing technology (few unknowns)

frugal and sensible appearance: feels flimsy, but not excessive

intentionally places Painter into the less expensive category

Here, a unit was estimated to be $2.00 to $4.00 (plus inserts), depending upon the same kinds of things as the first option.

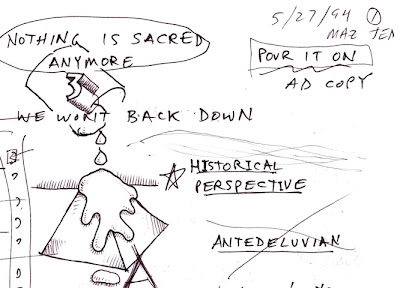

The third option was a startling one: a paint can. I could tell that the designers, who had brought all the options mocked up, were uneasy about this one. But the very fact that they had thought of it turned out to be a really great thing! Their comments were:

The third option was a startling one: a paint can. I could tell that the designers, who had brought all the options mocked up, were uneasy about this one. But the very fact that they had thought of it turned out to be a really great thing! Their comments were:a visual reference to paint: could be either clever/cute or corny/tiresome

stands out on retail shelf, but may not fit on standard displays

no set-up or tooling required

interesting and useful container after it has been opened

It worked out to between $0.75 to $2.00 per unit (plus labels and inserts), and it of course depended upon quantity and style of can.

This one was really different, we noticed. And it had a handle. I was thinking people walking away carrying a can of Painter. That seemed like a really noticeable thing: people would talk.

The fourth option was a wooden box. This was quite a distinctive look and the designers were quite proud they had been able to mock it up reasonably. Their comments were:

The fourth option was a wooden box. This was quite a distinctive look and the designers were quite proud they had been able to mock it up reasonably. Their comments were:- rustic, natural material has a "fine arts" appeal

- a reference to other containers found in fine art studios: wine crates/cigar boxes

- stands out on retail displays, but still fits on a bookshelf

- interesting and useful container after it has been opened

- heavy, substantial feel

- some unknowns because it has not been used for software packaging

It worked out to between $4.50 to $9.00 per unit (plus labels and inserts), and it of course depended upon quantity, type of wood, finish, size, assembly (nailing, stapling, gluing), type of lid (hinge or slide), and other things.

This one appeared to have a lot of unknowns and it could get messy. I was thinking: splinters!

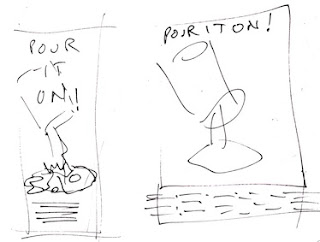

The fifth option was a cardboard box with an accordion display. This one was kind of out there. But they had a plan. It looked like it needed some kind of plastic cover to keep the accordion intact, and I wasn't sure there would be a simple story on how to display it. Their comments were:

The fifth option was a cardboard box with an accordion display. This one was kind of out there. But they had a plan. It looked like it needed some kind of plastic cover to keep the accordion intact, and I wasn't sure there would be a simple story on how to display it. Their comments were:- explains and shows off tools in a visually appealing way

- accordion could also serve as a quick reference sheet

- establishes a unique aesthetic which could translate to ads and brochures

- makes it appear larger on the retail shelf, but smaller on user's shelf

It worked out to between $1.00 to $3.00 per unit in addition to the cardboard box (plus labels and inserts), and it depended upon quantity, the style of the cardboard box, and the availability of the plastic frame.

I was thinking: manufacturing nightmare. Poor designers.

The sixth and final option was actually kind of interesting: an archival paper box. Their comments were perceptive:

The sixth and final option was actually kind of interesting: an archival paper box. Their comments were perceptive:

- has a fine arts look with a reference to caring about preserving quality

- is an exciting off the shelf product

- is single-vendor dependent

It worked out to between $3.00 to $4.50 per unit (plus labels and inserts), and it depended upon number of units and the thickness of the material.

This was a visually interesting box, but I was thinking: shelve it. It was for putting stuff away. For a long, long time. Not what I wanted for the software we were making.

So, how did we come to the paint can conclusion? Steve Thomas mentioned that, although he liked it, he had his concerns because it wouldn't fit on the typical retailer's shelf. I liked the paint can because it was so different. It seemed innovative. And I could get over the juxtaposition of fine art paint in a tube versus house paint in a can. I figured that, if you saw it, you would just think paint. Steve Manousos liked that it was inexpensive, that it could look quite good, and that there were probably lots of ways you could change it. Perhaps you could stamp Painter onto the lid.

We had a multi-hour long discussion about the ergonomics of the paint can. I fished a quarter out of my pocket and popped the lid of the can open. OK, you didn't need a screwdriver to open it. We looked inside. The designers had carefully cleaned out a paint can, so there wasn't a smell. We wondered about the size of the manual. We checked how many floppies could fit inside (this was before CDs were used for software delivery, and certainly before online delivery via download). I was keen on having some kind of poster with the product. We figured out that it would have to be rolled up inside the can as the first insert.

We knew once we chose the can, that we would have to go with ring-bound manuals, if they got past a certain thickness.

We knew once we chose the can, that we would have to go with ring-bound manuals, if they got past a certain thickness.

We figured that we might need a label for the top of the can. We debated whether or not we would show a little metal on the side of the can, or whether the label would meet itself.

When Painter shipped in September 1991, it was a labor of love. But it was the first can of many.

And when the can shipped, it was a little more shiny than the one shown here. More than twenty years have tarnished its surface.

I painted the image of the paint can on the label. It looked so realistic when printed that we were forced to put the text Image of the can was created with Painter at the bottom. We were concerned that people would think it was a real painting, totally defeating its purpose.

The Painter brush script was also provided by Rucker/Huggins. I'm not sure who actually did it, but I'm thinking Cleo. She was the designer responsible for Adobe's Sonata music font, by the way.

The Painter brush script was also provided by Rucker/Huggins. I'm not sure who actually did it, but I'm thinking Cleo. She was the designer responsible for Adobe's Sonata music font, by the way.It became necessary to create a new brush script numeral for each version of Painter. Here you see the version created for 2.0.

As time went on, we continued to repurpose real objects in new technological ways, the essence of skeuomorphism. The reason was obvious: people already knew how to use the real objects. So there was nothing to learn.

This philosophy worked its way into our design inside the program as well, with icons that looked like real brushes, pencils, erasers, and such. One of my favorite cases was the Painter 2.0 splash screen, shown here.

I might have mentioned that this look comes from a real book that lived on our shelf: The CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics.

As you can see, John Derry did quite a good job of simulating the leather-grain red-and-green look with the pressed-in gold detail.

As you can see, John Derry did quite a good job of simulating the leather-grain red-and-green look with the pressed-in gold detail.John obviously chose a warmer illumination when rendering his "book". It's uncanny!

And why did the can smell like fresh paint when it was opened? This was the result of the varnish layer on the poster, we understand.

One more thing about the can I should mention is that, for Painter 3, we wanted a golden look for the can and Steve Manousos had discovered that, normally, paint cans were varnished internally with a golden color sealer that didn't change the feel of the metal, but it did change its color. So we simply had the paint can maker turn the treated metal upside down and the result was that the gold was now on the outside instead of the inside!

We did finally do a metal emboss of the lid of the golden Painter 3 can with the Painter brush script. This actually saved us even more cost of goods, because we didn't have to print a label or glue it onto the lid! Simplicity is almost always the right answer!

More repurposing of real-worl objects: The Painter Power Palette Picker from the Painter 4 can. This came from an idea by Michael Everitt, an information design contractor. We knew that Pantone and other companies were showing their colors in this kind of format, so we decided that we would create a way to look at all the palettes and their options in a single quick-reference.

We were proud of our ingenuity. You could see all the art materials, look at the brush strokes over various images, get info on how all the palette UI worked, and of course there was a complete list of keyboard shortcuts.

Hmm. Some of those patterns look kind of familiar!

At some point, we will look at how the can progressed and what we did to keep it new and desirable.

And maybe a little about those posters...