Tiling patterns

Tiling patterns are the subject of an application I have written specifically for exploring the

San Marco Basilica tiling patterns I recorded in my notebooks in May, 1997.

The original tilings were simply sketched. This is not because I was without a camera. I certainly had a very good one with me. No, I sketched the tilings by hand because the church authorities would not allow photographs in the Basilica!

What mathematicians and others have done is to buy the post cards (I think I have a few of them as well), scan them, and post their pictures online. Usually as a challenge for students to determine which repeating group is represented in the tiling.

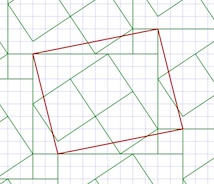

The pattern of five-square C-tiles from an earlier post of mine,

Different Perspectives, is seen here. This was an early test case for my new application, which I call

Tile Patterns.

This C-tile is one of the twelve pentominoes. All of the pentominoes can tile the plane in one way or another, though some of the tiling bases are a bit larger than this one.

For information on the grid, basis, and segments used to define the tiles, consult my last post,

Patterns, Part 5.

My test cases for this application make pretty designs. And some are rather busy in an op-art fashion.

Here is one, which has tiles that seem to simulate cut jewels, which must certainly qualify as a 1990's video game background!

This one broke my program a few times before I got it to work. Mostly because some of the polygons actually have holes in them!

Since the last post, I have implemented a few new things. Before, the application had the ability to set a grid, adjust and specify a basis parallelogram, and draw segments. As you draw, segments appear in all repeats of the basis area.

I have added the ability to divide up the segments when they touch or cross. Then I extracted a set of nodes (all on grid points) that bound each segment. Then I added the code to identify all closed polygon areas. As I mentioned, this includes some holes as well, particularly in the jewel tiling. Finally, the ability to specify the color for each closed polygonal area has been added. This allowed me to create all the tiling patterns you see here.

When I work this way, I only have to specify each polygon's color once, and all repeats of that polygon get colored. So I don't have to (laboriously) do the coloring in Painter. I get a cleaner result also. With this tiling, you can just see the parallelogram basis in red. Oops, I left it in!

Each of these patterns represents a new test case that broke the new application in some way.

The ability to save and restore patterns was the first feature I made. Then, when I built the extraction of polygons, I had to write save and restore of the polygons and their colors. This was an exercise in versioning, since I had saved several patterns already, but only the segments were stored.

Really what is needed (beyond what I have written so far) is the ability to maintain a palette of colors that is easy to pick from. And an easy way to deposit color into the polygons, with just a click.

The traditional way of doing this, along with adding segments, is a toolbox. Which is kind of passé, when you look at modern multitouch UI.

The ability to edit segments (in case I make a mistake) was another important feature to add.

Without that feature, I would have to clear and start over. Very troublesome!

So a segment selection and adjustment capability was necessary to implement. The requirement was either moving the entire segment or moving one of its ends. I just snapped the mouse point to the grid and looked for a segment end at that point.

For picking in the middle of a segment, I used a pick tolerance (really just a few pixels) to decide if I was close enough to the center of the line to pick it. Still, I had to implement point-to-segment distance, which is the only hard geometric computation.

Having implemented Shapes as part of Painter (and part of ColorStudio), I am very familiar with grid snapping and geometry editing. Actually very little coding was required.

I also used the San Marco Basilica tiling patterns as test cases. The first few patterns are really not as three-dimensional as some of the patterns. I think these were some of the first patterns laid down on the Basilica floor.

This pattern shows a black field with interspersed gray and light brown rectangles. Or you could view it as a checkerboard with turned gray squares inside the black ones.

The challenge for the tilers was to create diamonds that are just rotated squares. The larger light brown diamonds have an edge length that is sqrt(2) times larger than the smaller gray squares. That must have been fun.

The next pattern shows a lattice design.

This design has a brown field with small black squares inside it. Each black square has a gray diamond inside it.

Clearly, the later the tile work was designed, the more complicated it becomes. Notice here that the brown field is actually made of hexagons that interlock. It's hard to show that here, though.

In the real Basilica, the tiles are all made of marble. So there is a strong texture to all of them, and also quite a bit of color variation.

That may be the next thing for me to implement, to simulate the marble texture. Of course I have some ideas on how to do that. Also, simulating the grout will be of importance. That turns out to be pretty easy, since I already have a way to render that (as I showed in the previous post).

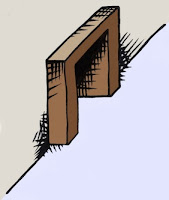

With this one, the patterns are getting a bit more three-dimensional.

There's just the suggestion of a square box with a white bottom. This is inside a kind of square corner.

Of course, all the tile work is two-dimensional since it is just a floor.

The tilers took on the challenge of making their work more and more three-dimensional with time. By the time we get to the renaissance, most of the designs were faux three-dimensional designs, as we will see with later examples. Perhaps this one is more like a coat of arms.

The next one shows a feature that is quite common on the Basilica floor: the checkerboard.

Checkerboard occur most commonly in frieze work (borders) and often go around curves on the Basilica floor.

This shows the artisan's skill more than ever.

This pattern is found on the floor, along with some that only feature four checkers on a side.

I figure the high contrast of the checkerboard was a visual stimulant. But in reality, the tilers were influenced by what they could get from the quarries. In the year this was made, there was probably a surplus of white and black marble.

No patterns on the Basilica floor are more striking, or more difficult to create, than the ones that feature circles.

Here I have approximated the circular arcs with polygons, but you get the picture.

The really cool thing about this one is the way the circles intersect each other so perfectly.

Oh, and by the way, you see the pattern is incomplete at the top. Its another bug I'm chasing! You will see this on three or four of the tile images in this post.

Nonetheless, this image shows the magic of tile patterns.

This shows another kind of tile pattern. I think the design has the downwards diagonals in a kind of three-dimensional design to indicate some kind of depth.

And traditionally, the black field allows you to see the other elements as objects on that field.

In this case, the black is less used for shading than for simple depth.

This is another example of a half-drop pattern, as it would be called in Painter. Half-drop patterns are typically used for wallpaper. But wallpaper is really not very long-lasting. Not compared with a marble tile floor, which has been known to last thousands of years.

This pattern was featured in my last post. Here the colors are a little closer to the actual pattern taken from the Basilica floor.

With this one, the illusion of depth and three-dimensional structure is excellent.

The black diamond tile is used to show the inside of a box. The top of the box is shown in two colors, giving it a kind of silvery sheen. The side of the box is in natural wood colors. In all, it is an exquisite pattern.

This one was probably sixteenth century.

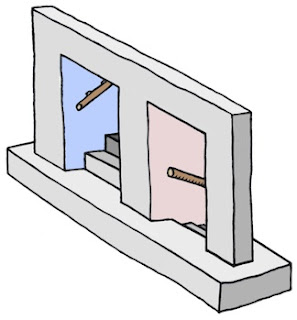

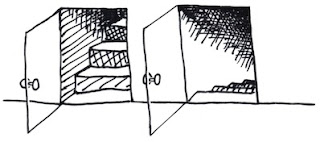

This next pattern shows clearly the three-dimensional structure.

The rendering of this pattern also shows clearly the grid at the top, the guide lines, and then the tile colors below.

Actually this is a bug, but I find it to be instructional.

With this pattern, the gray diamonds are the bottom of diamond-shaped pits. The white rectangles are the tops of the lattice. And something new: black diamonds form the intersections of the lattice.

It is visually interesting and also something quite new. Each tiling shows the style of its creator. It shows that the Basilica floor was designed by many artisans over the centuries, and that they were influenced by each other.

This tile pattern is an exquisitely detailed one. It is entirely three-dimensional. One thing about these tilings is that they have the concept of an

assumed light source.

This imposes a rule that allows the designer to consistently shade the shapes. Of course this means that several different colors of tile are needed. In varying quantities also!

Various pyramidal shapes inhabit this one and so you see it is a different kind of surface depiction than we have seen so far.

Like the black diamonds of the previous tiling, this one features smaller pyramids (or indentations?) at each intersection. So most likely this one was created after the previous one.

Minecrafters will probably recognize this pattern: the corner cube pattern.

It was certainly not invented in Minecraft, which certainly appeared a few centuries earlier on tile floors in Italy.

It shows most clearly that consistent shading is required to get the best illusion of three-dimensional shape.

This is one of my favorite patterns due to its simplicity and its optically convincing form.

So this pattern is one of the more mature three-dimensional forms, rivaled closely by the next pattern.

This pattern is like the previous, but entirely in pyramids.

Ever seen the pyramids at Giza in a satellite reconnaissance photo? What I want to see here are the

shadows of each pyramid being cast on their neighbors.

Well, perhaps that was beyond the thirteenth-century tile masters.

One thing needs mentioning. The tile patterns are quite similar to modern

quilt patterns. I have even seen some of the San Marco tile patterns worked carefully into quilts (even with the marbled textures in the cloth). I can imagine them in latch-hook rugs as well.

I think this tile pattern shows that the tile masters were both aware and interested in shadows. The black triangle

could be one facet of the three-dimensional geometry. But I think it's a shadow.

I see it as a shadow being cast into the trough that has been carved into the floor only in dark squares of the checkerboard pattern.

Walking on a floor with this kind of tiling, or in fact any three-dimensional depiction in a tile floor, would be a trip!

Literally. I would be worried about getting my foot caught in the apparent holes!

I found many depictions of this pattern on the floors in the old churches of Byzantium. This one differs from the earlier one both in color (four colors are used, subtly) and also in the angles of the squares.

Thus also in the width of the diamonds. They liked to use sixty-degree angles, so the diamonds would be "double triangles".

This one is shown at about fifty degrees. Mostly because I used a relatively small grid to construct it. It almost reminds me of the harlequin pattern, which is really only a diamond grid in a two-tone checkerboard. When you shade it in this way, it becomes three-dimensional, and can fool you into thinking it is a real surface.

This ornament is found on the floor at the San Marco Basilica. It is quite complex!

It reminds me of the American Indian rug patterns found at the Ahwahnee hotel in Yosemite.

But the Venetian tile floor will be still there long after the American Indian tapestries have turned to dust.

Unless, of course, global warming takes its toll and submerges the Piazza San Marco in the Adriatic.

In the meanwhile, let's keep the art and science of tiling patterns alive!

Patterns are a part of our lives. Our clothes, our wallpaper, our tapestries and hangings, our rugs, and many touchstones in our very existence show the influence of art and mathematics. The art of making patterns promotes spatial reasoning and creativity.

These are some of the reasons that I have featured textures and patterns in my blog. Also, of course, they dazzle our eyes and provide for wonderful illusions: the illusion of depth, the illusion of interlock, the illusion of spatial connectedness and completeness.

When a tiling pattern has a flaw, we automatically see it.

Patterns are literally built right into our consciousness.

To create a drawing of a basalt formation, I actually used a rendered Voronoi diagram, which you see here, transformed it into a subtle perspective, establishing two vanishing points. Then I made three copies arranged as layers in a way that approximated placing them on three-dimensional transparent layers at various depths. This was so I could see the levels, and so the third vanishing point could be right.

To create a drawing of a basalt formation, I actually used a rendered Voronoi diagram, which you see here, transformed it into a subtle perspective, establishing two vanishing points. Then I made three copies arranged as layers in a way that approximated placing them on three-dimensional transparent layers at various depths. This was so I could see the levels, and so the third vanishing point could be right. Next, on a new layer, I drew lines on top of the the lines that I wanted to represent the three-dimensional surface of the basalt formation. This meant choosing a three-dimensional height for each cell. The base layer that extended to the outside of the drawing was the lowest height, of course, and a second and third layer was built on top of it.

Next, on a new layer, I drew lines on top of the the lines that I wanted to represent the three-dimensional surface of the basalt formation. This meant choosing a three-dimensional height for each cell. The base layer that extended to the outside of the drawing was the lowest height, of course, and a second and third layer was built on top of it. I used an extra transparent layer (behind the layer with the lines) and marked each cell with a three-dimensional height index so I could be sure which heights corresponded with each cells. This told me where to put the shading and also told me how to interpret the extrusion lines.

I used an extra transparent layer (behind the layer with the lines) and marked each cell with a three-dimensional height index so I could be sure which heights corresponded with each cells. This told me where to put the shading and also told me how to interpret the extrusion lines. That only took a few days.

That only took a few days. I used woodcut shading to create shadows and accessibility shading. This created a very nice look.

I used woodcut shading to create shadows and accessibility shading. This created a very nice look. The final step was coloring the tops and the sides, using a gel layer.

The final step was coloring the tops and the sides, using a gel layer.